For centuries, cultures across the globe have crafted various stories and myths about strange cross beings. The dog-headed men, or Cynocephali, are among the strangest and most famous beings in human history.

The word Cynocephali derives from the Greek word kynokephaloi (κύων, kyōn – dog; κεφαλή, kephalē – head).

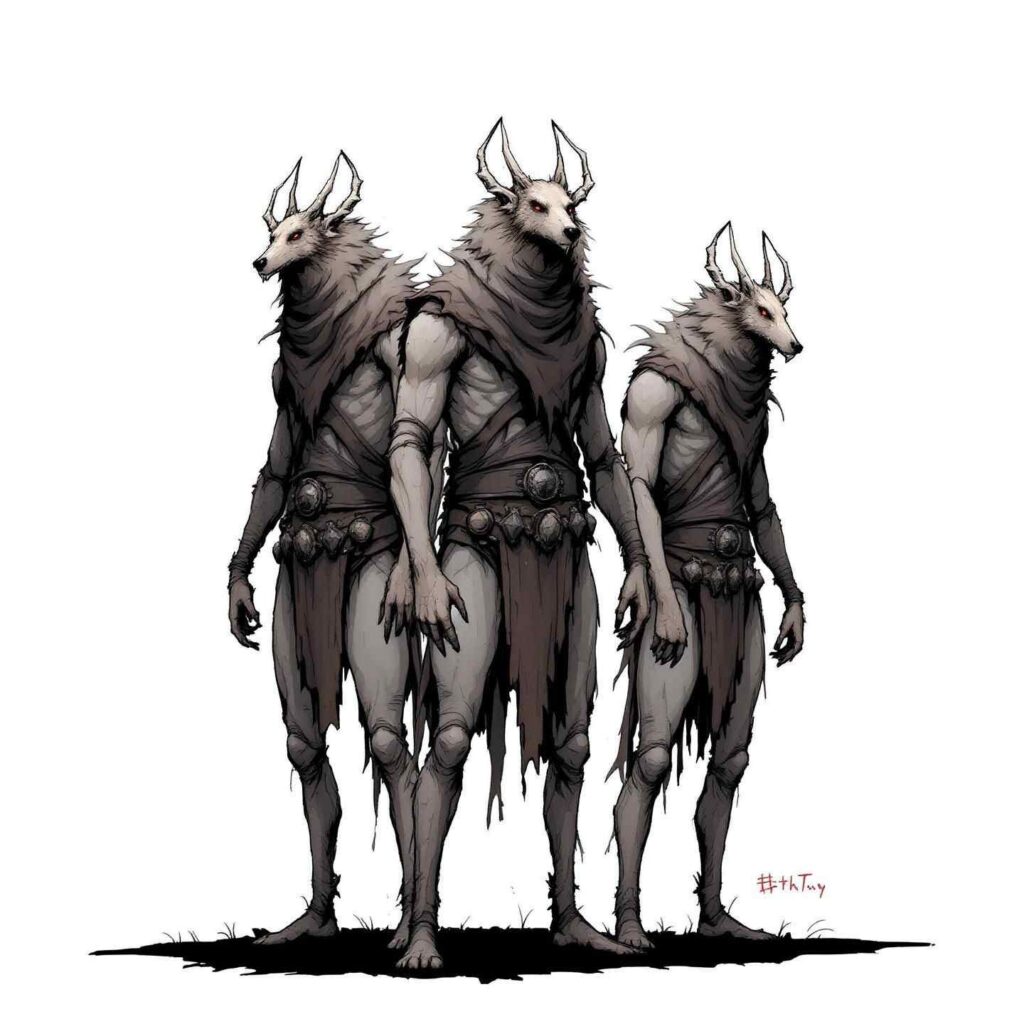

They are usually described as having a human body and a dog’s head.

They appear in religious texts, folklore, medieval maps and in travelers’ writings.

In this article, we will discuss the history of the Cynocephali as well as the constructed views of them within various cultures, critique their roles in historical texts, and attempt to theorize why they remain of special interest to us.

Contents

- 1 Origin of the Myth of the Cynocephali

- 2 Ancient Greek and Roman Accounts

- 3 Medieval Europe and Christian Context

- 4 Geographic Placement: Always on the Edge

- 5 Cynocephali in Religious Symbolism

- 6 Linguistic Themes: Barking vs. Speaking

- 7 Cynocephali as Metaphors

- 8 Cynocephali in Modern Pop Culture

- 9 Why Cynocephali Still Fascinate Us

- 10 Legacy of the Cynocephali

Origin of the Myth of the Cynocephali

The myth of the Cynocephali goes back to the oldest civilizations of man. The ancient Egyptians may have been the first to portray gods with animal heads.

Anubis, the jackal-headed god of embalming and the afterlife, is often evoked as the earliest form of the dog/bipedal human hybrid archetype.

However, it was Greek authors who began to write about them as real tribes or races, not as deities. And they were not even describing entire nations; they were describing whole peoples.

The myth began to transition from one of the divine to one of the anthropological, with these creatures described as exotic human inhabitants of unknown lands typically at the fringes of geographers’ maps and knowledge.

Ancient Greek and Roman Accounts

A number of classical authors documented first-hand, or second-hand accounts of these beings.

Ctesias is the most cited author, a Greek physician and historian who was affiliated with the Persian court in the fifth century BCE.

Ctesias described them in a written work about India, a distant and mysterious land.

He described them as fierce “barking men,” who dressed in animal skins, hunted savage beasts, and ate raw meat.

Besides defining features of their five senses, Ctesias described these dog-headed figures in detail as intelligent creatures with social organization, even with their animal-like appearance.

Pliny the Elder included them in his encyclopedias including Natural History, and, like Ctesias, Pliny identified them as dog-headed men from territories surrounding India and Ethiopia.

Pliny also reported that they could not speak human language, and typically communicated with barks and gestures.

While the authors described them as abhorrent creatures, they consistently conveyed possible noble, even human customs and characteristics attributed to them.

This provides interesting connections between human or animal forms, and the representation of character.

Medieval Europe and Christian Context

As we enter the medieval period in Europe, the understanding of these beings begins to shift again.

They are seen as more than mere exotic outsiders and are woven into the Christian imagination.

To write about them specifically, the stories began to get moralized and interpreted spiritually.

The dog-headed men began to represent either man’s corrupted nature or the redeemable qualities of even the most beastly beings.

One of the most interesting facets of medieval lore is the association of St. Christopher with this race.

Even in some Eastern Orthodox and apocryphal texts, St. Christopher was first depicted as a dog-headed man who converts to Christianity and is later martyred.

While the Western Church rejected this reading, the suggestion of holiness in a monstrous person is a powerful message of the transformative and redemptive potential of faith.

The follow duality—savage vs. saint—allows this hybrid race to capture the tension between the known and unknown, the civilized and the wild, and even the human and the animal.

Geographic Placement: Always on the Edge

Across ancient and medieval literature, these figures were positioned at the edges of the known world.

Be it in India, Africa, Scythia, or even the Arctic, they were dangerous and remote.

In the margins of medieval maps, especially the mappa mundi, cartographers placed monstrous races in unknown territory.

There was a cultural and psychological function to this positioning.

The lack of familiarity of geography of far-off lands was proximate to the imagination.

Filling in these spaces with strange beings added to the danger and wonder of distant lands.

Cynocephali in Religious Symbolism

These dog-headed people also appear in the genre of apocalyptic literature as well as in hagiography beyond St. Christopher.

In these texts, they could be represented as one element of God’s bigger creation or threats to Christian civilization.

Some theologians struggled with the question of whether they could have souls, or whether they were human at all.

When St. Augustine wrestled with this very issue in The City of God, he debated whether or not monstrous races, such as these, proceeded from Adam as the rest of humanity, or whether or not they were part of some other creation altogether.

Augustine suggested that if they had the ability to reason, they had to be human, and therefore eligible for salvation.

This speculation in theology suggests just how seriously early thinkers considered the myth.

These dog-headed figures were not simply fiction or fables; they belonged to a broader cosmological discussion about issues of humanity, faith and divine design.

Linguistic Themes: Barking vs. Speaking

A consistent feature in narratives surrounding them is how they communicate with each other; they are detailed to bark, howl, use movements, etc. instead of speaking.

Because their communication behavior is at odds with humans in this way, it reinforces their alienness and ‘non-human’ status.

Speech counted as a sign of civilization in ancient cultures.

Those who could not “speak properly” were usually perceived as uncivilized or even subhuman.

By promoting these beings as subhuman, the ancient writers reinforced the cultural superiority of their own societies by producing literature that suggested they were inferior creatures.

However, in some versions of the legend, they can understand language and follow rules.

Sometimes their behavior is described as being more ordered than humans.

All of this makes the assertion that speech is an essential feature of humanity problematic.

Cynocephali as Metaphors

While people may have literally believed in dog-headed men, these creatures have been used as metaphors across forms of art and literature.

In some formulations, they reflect the wild-side of humanity—our instincts, our aggression, our rawness.

The proposition of their animal head with a human body portrays the back and forth struggle between rational minds and our base desires.

In other forms, they represent foreign peoples. They appear as strange people that cannot communicate in a recognizable language.

It illustrates how ancient societies viewed others that were outside their linguistic or cultural sphere.

Seen in this form, the myth reflects a much earlier form of “othering”, where we define ourselves in contrast to an imagined monster that is considered the opposite of everything that is human.

Cynocephali in Modern Pop Culture

Though we no longer think there are dog-headed men on the fringes of our maps, the myth of these hybrids survives in today’s popular culture.

These beings are included in fantasy novels, video games, and table-top role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, which commonly include hybrids.

While most depictions are way more vibrant than what is described in ancient texts, we still see them portrayed as having strength, fierceness, loyalty, and a mysterious connection to man and beast.

Some are guardians, some are warriors, and some have been cursed.

All in all, the story survives as a source of creativity—new interpretations of this myth, while staying true to it.

The longevity of their legend shows how stories rooted in ancient mythology can be reinvented and reinvigorated in modern narratives.

Why Cynocephali Still Fascinate Us

These mythic figures continue to fascinate human imagination in an era when science has explained most of the same old mysteries, but we can merely speculate why.

It is their deep symbolic significance. They embody two fundamental aspects of human being: man and beast, mind and nature, self and other.

They draw a living tension around man’s ceaseless struggle with identity, morality, and civilization itself.

Whether one accepts them as monster or friend whose intentions remain still mysterious and misunderstood, these monsters live on because they elicit something in us,

Our curiosity about the other, our dread of what is not known, and our fascination with the monster.

Legacy of the Cynocephali

The myth of these dog-headed people has been around for thousands of years in ancient texts and modern fantasy.

Whether seen as savage natives, divine messengers, or simply misunderstood, they have left a paw print on human imagination.

Their legend keeps evolving in ways that speak about the past as living historical artifacts.

This myth is present in a past millions of years old, it continues to evolve based on every generation, with new stories, new fears, and new hopes replacing old ones.

As long as humanity is fascinated with the edge of the map—the unexplained or the unknown—the Cynocephali will survive.

2 thoughts on “Cynocephali: Dog-Men from Ancient Lore”