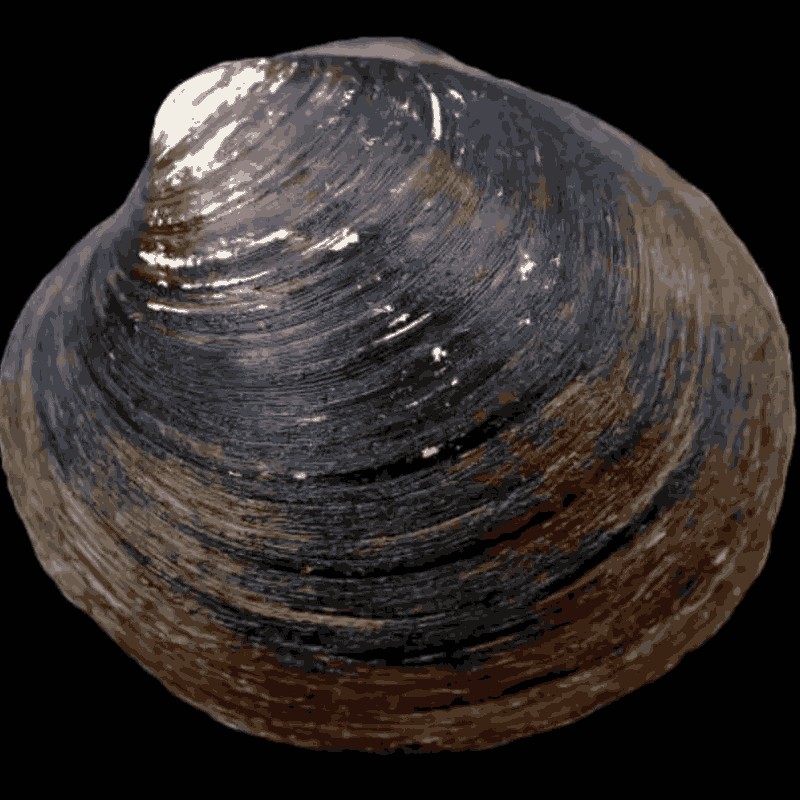

In the chilly, cold waters off the coasts of Iceland in 2006, scientists made an incredible discovery—an ocean quahog clam (Arctica islandica) that will ultimately be confirmed to be the oldest living animal EVER recorded. Aptly named Ming the Clam, since the clam was born during China’s Ming Dynasty, this seemingly unremarkable bivalve was estimated to be over 507 years old.

What should have been a moment of great distinction in scientific discovery, became a tragic moment in science. In the course of a routine research procedure, Ming the Clam was killed by the very researchers who “discovered” it!

This article discusses how Ming the Clam was killed, why it mattered so much to science, and what the researchers learned from the experience.

We will look at how scientists determined the clam’s age, and why it was such a shock to the scientific community, and how this clam became a symbol both of discovery, and also with that discovery came an unexpected loss.

Contents

Who Was Ming the Clam?

Ming the Clam was part of the species Arctica islandica, which is known as the ocean quahog.

They have an incredible lifespan, living for centuries at a time, because of their slow metabolism and their habitats are stable cold-water regions.

Ming the Clam was discovered in 2006 while researchers from Bangor University in Wales were studying marine climate change.

Greenwich, while on a research boating trip shoveling up clams from the bottom off the coast of Iceland, where ocean quahogs are abundant.

The researchers at first thought the clam was around 405-year-old, but with their aging methods, found out years after that the clam was in fact, 507 years old – that is it was born in approximately 1499, during the period of the Ming dynasty in China, hence the name.

This made Ming the Clam the oldest non-colonial, or an individual, animal ever to be found – even surpassing the biological lifespan of the oldest and long-living tortoises, whales, and trees.

How Scientists Determined Ming’s Age

To estimate Ming the Clam’s age, scientists used a method called sclerochronology.

Sclerochronology is a similar method to dendrochronology in that species that develop a calcareous shell also develop growth rings on shell surfaces and cross-sections.

Ocean quahogs produce one visible growth ring per year. The rings form on both the outer surface of the shell and the cross-section of the shell.

Each growth ring is formed according to seasonal changes in the oceanic environment, such as temperature and nutrient availability.

At first, scientists counted the rings on the outer surface of the shell and determined that Ming, at 405 years old, was the oldest marine bivalve to have ever been recorded in history to date.

But, in 2013, the scientists would reanalyze the individual shell by cutting into the shell and conducting an internal ring count, together with radiocarbon dating methods, which ultimately adjusted Ming’s age to 507 years old.

This finding represented a watershed moment for marine biology because it was representative of the amazing lifespan of quahogs,

but it also represented a living account of oceanic history for a period of over 500 years, in one shell.

The Accidental Death of Ming the Clam

Unfortunately, Ming the Clam met a tragic end. Shortly after collection for scientific characterization,

Ming (along with the many other ocean quahog specimens) was frozen to allow researchers to preserve its tissues.

Ming was frozen with potentially hundreds of other clams… before anyone knew how old Ming was.

No one intended for Ming to die. They were all simply acting out a process that was a standard protocol, as part of a larger research project,

where researchers wanted to track seasonal climate patterns using shell growth data.

The age of Ming had not been established when collected, and only after dissection and a cool,

calm analysis were they faced with the undeniable science that they had killed the world’s oldest animal ever recorded in science.

There is a sense of irony in all this and the scientific community and the internet didn’t ignore it.

That which was intended to be a remarkable biological discovery, now became an example of unintended consequences.

Public Reaction

When the news broke of Ming’s age—and accidental death—an overwhelming rush of reactions ensued on the internet.

Many were exasperated. Some accused the researchers of “murdering history.” Others joked that Ming survived the Black Plague, both world wars,

The industrial revolution, and thousands of marriages, only to be frozen by inquisitive humans.

Reddit users and commenters offered funny and sarcastic takes:

“To survive 500 years of natural threats and then get thawed and counted in a lab.”

“They opened it just to count the rings. How terribly tragic.”

“He survives five centuries of threats only to be Ming slaughtered.”

This mix of awe, tragedy, and human makes Ming the Clam, a meme worthy legend, and its name will certainly live on long after death.

Why Ming the Clam Matters to Science ?

Ming the Clam’s passing is regrettable but it does provide some useful scientific implications.

Ming the Clam, and its cousin the ocean quahog is a climate proxy.

The shell of the ocean quahog (or the clam) holds a sulphur record for everything from sea temperature, salinity, and nutrients from the sea allowing us to reconstruct a climate record going back hundreds of years.

When scientists analyse the chemistry of the shell growth rings (much like a tree refers to its), they can:

- Study changes in the ocean through time.

- Examine the long-term effects of climate change.

- Investigate biological-ageing and the resistance to metabolic disease.

Ming’s age brought with it other new questions:

- Why do some animals age so slowly?

- How do cells contrive to avoid ageing for hundreds of years?

- What unique aspects of their biology can be useful for humans?

These types of queries are still currently being explored.

Controversy and Ethics in Scientific Research

The situation with Ming the Clam raises an ethical question in biological research.

How do we reconcile the aiming to discover something, and to care for life?

In fact some critics said that a better care, or protocol for age estimation, meant Ming lived.

Some also defended the research group, of course, and said, well, ocean quahogs are not endangered and storing frozen would have not been difficult. But what is to say even about Ming’s death, it was all bad?

Anyways, the case raised some more questions of research protocols, and enlivened discussions around three streams of consideration in decision-making:

- the ethics of non-invasive means of doing research,

- conservation of rare, or ancient specimens.

- acting with regard towards other living beings, and not just research data.

The death of Ming was an unfortunate but valuable chance.

Ming’s Legacy

Ming the Clam is gone, but its shell is preserved in the National Museum Cardiff in Wales. The shell is used scientifically and educationally.

Many biology classes refer to the case study as an example of marine aging and how to be responsible scientists.

Since Ming died, scientists have found additional ocean quahogs that were over 400 years old — none of them have been as old as Ming.

In the popular imagination, Ming has become a symbol of biological endurance and human error.

It has motivated some documentaries, short videos, blog posts, and Reddit threads that are still being shared years later.

Conclusion

Ming the Clam was more than an old clam shell. It was a glimpse into Earth’s history, a biological wonder, and a reminder to think ahead.

While the fact that it died accidentally is a tragedy, it will have meant something.

It provided scientists with what they thought they wanted to learn about longevity, climate change, and the necessity of thinking mindfully about research.

Ming the Clam will finally be remembered not for its age but for the story that came from it. A story of amazement, irony, and scientific humility.

3 thoughts on “Ming the Clam’s Accidental Death Explained”