For centuries, the Devil’s Bible Codex, also called the Codex Gigas, has fascinated historians, theologians, and curious minds around the world. This 13th-century manuscript towers above other medieval books in both size and reputation. It embodies a striking paradox — blending the sacred with the sinister, faith with fear.

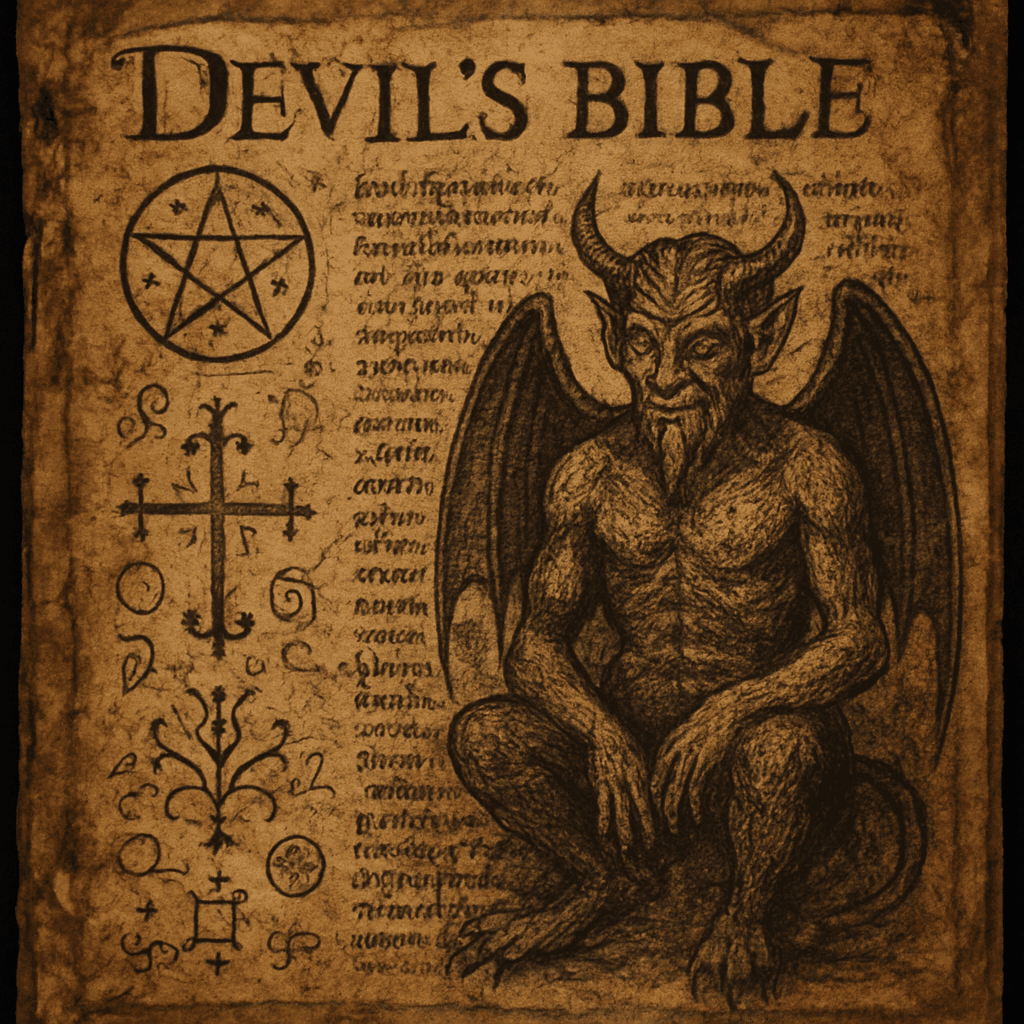

The Codex Gigas, Latin for “Giant Book,” is no ordinary manuscript. It measures nearly one meter tall, weighs over 75 kilograms, and is bound in thick leather reinforced with metal. Its massive size alone is impressive. But the nickname “The Devil’s Bible” comes not from its scale, but from the mysteries it holds. Its origin is enigmatic, its contents unusual, and most famously, it contains a full-page illustration of the Devil. These features have made it one of history’s most captivating enigmas.

Contents

- 0.1 A Book Born in Shadows

- 0.2 Between Heaven and Hell

- 0.3 A Testament to Human Ambition

- 0.4 The Allure of the Forbidden

- 1 The Origins of the Codex Gigas

- 2 Physical Description: The Largest Medieval Book Ever Made

- 3 The Scribe Behind the Legend: Who Was Hermann the Recluse?

- 4 Unlocking the Pages: Contents of the Devil’s Bible Codex

- 5 Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Devil’s Bible Codex

A Book Born in Shadows

The origins of the Devil’s Bible Codex date back to the early 13th century in what is now the Czech Republic. At that time, monasteries were the main centers of learning and manuscript production. According to legend, a Benedictine monk at the Podlažice Monastery — a small and impoverished community — created the manuscript.

Facing the ultimate punishment for breaking his vows — being walled alive — the monk promised to compile a book containing all human knowledge in a single night. His goal was to atone for his sins and honor his monastery.

As midnight approached, the task proved impossible. Desperate, the monk allegedly made a pact with the Devil, offering his soul in exchange for supernatural help. By morning, the manuscript was complete. In gratitude — or perhaps as a signature — the monk included a striking full-page portrait of Satan.

This haunting legend gave the Devil’s Bible its famous name. For generations, monks, scholars, and rulers regarded the Codex with both awe and fear. While historians now agree the manuscript took many years to complete, the tale of the monk’s infernal bargain remains one of medieval Europe’s most enduring stories.

Between Heaven and Hell

The Codex Gigas is a monument to the duality of medieval faith — a fusion of sacred devotion and forbidden knowledge. It contains the entire Latin Vulgate Bible, historical chronicles, medical treatises, and even magical spells and exorcism formulas. On one page, the reader finds prayers and psalms; on another, instructions for summoning and banishing spirits. Opposite the fearsome image of the Devil lies a radiant illustration of the Heavenly City, representing divine salvation. This juxtaposition of Heaven and Hell has long fascinated scholars, who see it as a profound reflection of the human struggle between sin and redemption.

A Testament to Human Ambition

Beyond its religious and mythical significance, the Devil’s Bible Codex is a true masterpiece of medieval craftsmanship. Every letter was carefully hand-written in Latin with calligraphic precision. Elaborate initials and vibrant decorations illuminate its pages, making the manuscript a visual as well as textual wonder.

The Codex contains over 310 sheets of vellum made from calfskin, and astonishingly, it was created by a single scribe. This remarkable feat required immense endurance, patience, and discipline.

Modern paleographic studies confirm that the handwriting remains remarkably uniform throughout the manuscript. This consistency suggests that one person devoted decades of their life to completing it. Driven by repentance, obsession, or sheer devotion, the scribe created one of the most breathtaking literary monuments of the Middle Ages.

The Allure of the Forbidden

The story of the Devil’s Bible Codex endures not only because of its physical grandeur or religious content, but because it touches something primal in the human imagination. It embodies the tension between light and darkness, salvation and damnation, the sacred and the profane. Every culture has tales of forbidden knowledge and pacts with dark forces, but few are as tangible, beautifully crafted, or historically grounded as this manuscript.

Today, the Codex rests safely in the National Library of Sweden, preserved under carefully controlled conditions. Researchers and the public can also access it digitally. Even with modern technology and analysis, the Codex Gigas remains a mystery — an artifact where faith, art, and myth intertwine.

Over the centuries, the Devil’s Bible has become more than just a book. It is a symbol of humanity’s eternal curiosity, our desire to understand the divine, and our temptation to explore the forbidden. It reflects the human condition itself: capable of creation and destruction, of prayer and sin, of light and shadow.

The Origins of the Codex Gigas

The origin story of the Devil’s Bible Codex, or Codex Gigas, lies in a world where devotion, superstition, and scholarship often blurred together. To understand this extraordinary manuscript, we must journey back to early 13th-century Bohemia, in the heart of medieval Europe — a land of castles, monasteries, and mysticism.

The Monastic World of Bohemia

During the Middle Ages, monasteries were more than places of worship; they were centers of learning and cultural preservation. Monks acted as guardians of knowledge, carefully copying sacred and secular texts by hand. Among these monastic communities was the Podlažice Monastery, a small Benedictine house near modern-day Chrudim in the Czech Republic. Unlike the grand abbeys of France or Italy, Podlažice was poor, remote, and had only a few monks.

It was here, according to legend and limited historical records, that the Devil’s Bible Codex was created around the year 1229. While scholars still debate the exact date, paleographic evidence suggests it was written in the early to mid-13th century.

The Legend of the Damned Monk

The most famous legend associated with the Codex Gigas revolves around a Benedictine monk named Hermann the Recluse (Hermannus Inclusus). According to the tale, this monk broke his solemn vows — perhaps through pride, disobedience, or blasphemy — and was condemned to an unimaginable punishment: being walled alive within the monastery.

Desperate to save his life, Hermann proposed a miraculous bargain. He promised that, in exchange for mercy, he would create a single book containing all human knowledge — including the Bible, historical records, medical texts, and mystical secrets — and that he would finish it in just one night.

As midnight approached and the impossible task loomed, the monk, overcome by despair, allegedly turned to Satan instead of God. In exchange for his soul, the Devil granted him supernatural assistance. By dawn, the enormous Devil’s Bible Codex was complete, and as a tribute to his dark helper, Hermann painted a haunting full-page portrait of the Devil.

Though there is no historical evidence for this story, it became inseparable from the manuscript’s identity. The chilling legend likely arose from the book’s eerie contents and the striking contrast of holy texts with demonic imagery. Over time, Hermann’s mythical pact elevated the Codex Gigas from a simple manuscript to a symbol of forbidden knowledge and dark craftsmanship.

Historical Evidence and Reality

Legends aside, modern scholars have unearthed enough evidence to construct a more grounded origin story. The manuscript’s Latin text, script style, and decorative elements all indicate that it was written by a Benedictine scribe trained in the early 13th century. While the Podlažice Monastery may have been too small and poor to produce such a monumental work entirely on its own, it likely served as the home or starting point for its creation.

A note on the first page of the manuscript records that in 1295, the monks of Podlažice pledged the Codex to the Sedlec Monastery, possibly as payment for debts. Later that same year, it was repurchased by the Benedictine Monastery of Břevnov, near Prague. These early transactions suggest that the book’s immense value was recognized from the start — both materially and spiritually.

The Codex’s journey from one monastery to another also reflects the turbulent religious and political environment of medieval Bohemia. Monastic communities often exchanged valuable manuscripts, not only for scholarly reasons but also to gain prestige and influence within the Benedictine Order.

The Enigma of a Single Hand

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Devil’s Bible Codex is that it was written entirely by a single hand. Extensive paleographic studies, notably those by British scholar Michael Gullick, show that the handwriting is consistent from start to finish. There is no variation in ink, pen pressure, or letter formation, which confirms that no other scribes contributed to the manuscript.

This fact adds to the Codex’s mystery rather than resolving it. For a single person to create a manuscript of over 620 pages of Latin text — all perfectly uniform — would have required decades of relentless work. Gullick estimated that if a monk wrote six hours a day, five days a week, completing the Codex would take 25 to 30 years. Such dedication transforms the manuscript from a scholarly achievement into a lifelong labor of devotion, penance, or perhaps obsession.

Between Fact and Faith

While the historical evidence paints a picture of a devout and disciplined scribe, the legend of the Devil’s pact endures for good reason. Medieval culture was steeped in symbolism and the belief that the divine and demonic were ever-present forces. The creation of something so vast and magnificent could easily be interpreted as supernatural — especially when it contained both sacred scripture and forbidden magic.

The Devil’s Bible Codex, therefore, exists at the intersection of fact and faith, reason and superstition. It is at once a triumph of human endurance and an artifact haunted by myth. Whether born from piety or pride, the book’s creation story reminds us how thin the line was between holiness and heresy in the medieval imagination.

A Testament to the Medieval Mind

The Codex Gigas reveals much about the worldview of 13th-century Europe. It was a time when knowledge was sacred, and books were living vessels of divine truth. To produce such a massive tome was to approach the act of creation itself — an endeavor that blurred the boundary between human and divine capability.

In that sense, the Devil’s Bible Codex is not merely the product of a monk or a monastery. It is the reflection of an age that believed that knowledge carried both salvation and danger, that writing itself could summon either the light of God or the shadow of the Devil.

Physical Description: The Largest Medieval Book Ever Made

If the legends surrounding the Devil’s Bible Codex stir the imagination, its sheer physical presence leaves no less an impression. Standing before it today in the National Library of Sweden, one is struck first not by the mythical illustration of the Devil, but by the book’s immense, almost supernatural size. It is less a manuscript than a monument — a cathedral of ink and parchment that embodies the medieval ambition to contain all knowledge within a single volume.

A Giant Among Manuscripts

The Codex Gigas is, without exaggeration, the largest surviving medieval manuscript in the world. It measures approximately 92 centimeters (36 inches) tall, 50 centimeters (20 inches) wide, and 22 centimeters (9 inches) thick, and it weighs an astonishing 75 kilograms (165 pounds). To open it is to face a massive expanse of vellum — pages so large and luminous that they almost resemble thin sheets of marble.

The manuscript is composed of 310 leaves of vellum, which would have required the skins of at least 160 calves or donkeys. Each animal could provide only two sheets of such immense size. In a time when parchment was a costly commodity, the mere procurement of so much material represented an enormous economic and logistical challenge, especially for a modest monastery.

The vellum pages are unusually well-preserved, their creamy tone and supple texture bearing silent witness to centuries of care. Even after 800 years, the black and red inks retain much of their contrast, and the ornate initials that adorn the biblical texts remain vibrant with intricate patterns of blue, green, and gold.

Craftsmanship and Materials

The binding of the Devil’s Bible Codex is as formidable as its contents. The book is enclosed within two massive wooden boards covered in white leather, once polished to a fine sheen. Five metal plates — one at each corner and a central one in the middle — decorate and reinforce the covers. Each plate bears engraved motifs of griffins, symbols of vigilance and divine power.

Projecting knobs at the center of these plates served a practical purpose: they allowed the book to rest flat on its back without the leather touching the surface, reducing wear and damage. Small holes on the back cover indicate that the Codex was once chained to a desk or lectern, much like other sacred or precious volumes of the Middle Ages. This ensured both its safety and its symbolic immovability — a reminder that sacred knowledge was not meant to wander freely.

The parchment’s preparation would have been a painstaking process in itself. Each sheet had to be scraped, soaked, dried, and polished with pumice before receiving the carefully measured ink. Scholars have noted that the vellum in the Codex Gigas is remarkably even in thickness and color, a testament to the scribe’s meticulous craftsmanship and the likely assistance of skilled parchment makers.

The Calligraphy: Uniform Perfection

One of the most astonishing features of the Devil’s Bible Codex is the absolute uniformity of its script. Each line of text is written in a consistent form of Carolingian minuscule, a script that was clear, elegant, and widely used in monastic writing. The letters are upright and evenly spaced, showing none of the fatigue, sloppiness, or variation one might expect in a manuscript that could have taken decades to complete.

This perfection supports the theory that a single monk, working methodically and with almost superhuman patience, penned the entire book. The margins are wide and precisely ruled, the alignment impeccable. Even the ornamental initials — bursting with flowers, animals, and geometric spirals — display a consistency that suggests not only skill but a deep artistic vision.

The text itself is written in two columns per page, each column containing about 106 lines. Such density maximizes the use of space while preserving readability, another mark of practical genius. Red ink is used for headings, titles, and emphasis — an ancient tradition known as rubrication, from which the term “to rubrify” (to mark in red) originates.

The Illustrations: Windows to the Medieval Mind

While the Codex is primarily a textual work, its illustrations and decorative art elevate it to an illuminated masterpiece. Among the most famous images is the full-page portrait of the Devil — a grotesque figure with greenish skin, red horns, clawed feet, and a serpent’s tongue, crouched against a dark background. His face is both monstrous and strangely human, inviting endless interpretation.

Opposite this terrifying image is a depiction of the Heavenly City, rendered in calm tones of blue and gold, representing divine perfection and salvation. The contrast between these two pages — good and evil, heaven and hell — has fueled centuries of fascination and theological reflection.

The rest of the manuscript features elaborate initials that mark the beginning of each book of the Bible and major texts. These initials are richly decorated with zoomorphic and botanical motifs — intertwined dragons, flowers, vines, and even human faces — symbolizing the interconnectedness of creation. The color palette, though limited by the era’s pigments, shows mastery of composition and balance.

Trimmed by Time, Preserved by Fire

Originally, the Devil’s Bible Codex may have been even larger. When it arrived in Sweden in the 17th century, it was slightly trimmed — about one centimeter from the edges — likely to repair damage or fit a new binding. Yet, despite its long journey through wars, fires, and centuries of handling, the manuscript remains remarkably intact.

Its most dramatic moment came during the Stockholm Palace fire of 1697. As flames consumed the royal library, someone — whose name is lost to history — threw the Codex Gigas out of a window to save it. The fall injured a bystander but preserved one of the world’s greatest manuscripts from destruction. Today, scorch marks still linger faintly on some pages, silent scars of its near-death and survival.

Symbolism of Monumental Scale

Why create a book of such extraordinary size? Scholars propose several interpretations. Its monumental form may have been a statement of devotion, a physical embodiment of the scribe’s penance or faith. Others suggest it was meant to awe and humble those who saw it, reinforcing the power of sacred knowledge. The Codex Gigas could also have served as a liturgical or ceremonial book, read aloud during important monastic events or displayed as a testament to the monastery’s prestige.

Whatever its intended purpose, its massive scale ensures one thing: the Devil’s Bible Codex was never meant to be hidden away. It was meant to be seen — and to inspire reverence, wonder, and fear in equal measure.

The Scribe Behind the Legend: Who Was Hermann the Recluse?

Every great mystery has a human story at its core. Behind the towering pages of the Devil’s Bible Codex, beneath its layers of myth and medieval superstition, lies a single figure whose identity continues to intrigue scholars and storytellers alike — Hermann the Recluse, or Hermannus Inclusus as the manuscript later names him.

But who was this mysterious monk? Was he truly a man who made a pact with the Devil, or a disciplined scribe whose devotion outlasted his lifetime? To unravel the truth, we must look at both the evidence written in ink and the legends whispered through centuries.

A Name Written in Mystery

The only name associated with the Codex Gigas appears near the end of the manuscript: “Hermannus Inclusus,” which translates roughly to “Hermann the Hermit” or “Hermann the Enclosed One.” This title may refer not to a surname, but to a monastic state — a person who chose, or was ordered, to live in seclusion for spiritual reflection or penance.

Such reclusion was not unusual in medieval monasteries. A monk might voluntarily withdraw from the communal life to live as an anchorite, dedicating his existence to prayer, contemplation, and repentance. However, in Hermann’s case, his solitude may have been one of punishment rather than choice — a confinement imposed for breaking monastic vows.

Some medieval chroniclers suggested that Hermann’s isolation was part of an atonement for grave sins, perhaps even heresy. Others speculated that he was a monk of extraordinary skill, set apart by the abbot to undertake a holy task that no one else could accomplish. Whatever his true circumstances, Hermann’s seclusion gave him the time, discipline, and motivation to produce a work of unparalleled magnitude.

The Psychological Puzzle of the Single Scribe

Creating the Devil’s Bible Codex was not merely an act of writing — it was a lifetime of labor. The book’s flawless consistency indicates a man of exceptional precision, patience, and focus. To write 620 pages in neat, uniform calligraphy without a single major correction would have required decades of continuous work.

Paleographers estimate that if Hermann wrote for six hours a day, every day, he might have completed the manuscript in 25 to 30 years. Over such a span, handwriting naturally evolves as the body ages and muscle memory shifts — yet in the Codex, the script remains astonishingly constant from the first to the last page.

This uniformity suggests something deeper than skill: an almost meditative commitment to the task. Hermann may have regarded the creation of the Codex as a form of lifelong prayer, a way to reconcile himself with God or cleanse his soul from guilt. In this light, his supposed pact with the Devil becomes a symbolic myth born from the sheer extremity of his devotion — an acknowledgment that such superhuman effort seemed impossible without supernatural aid.

The Legend of the Midnight Pact

The story most people know about the Devil’s Bible Codex comes not from evidence, but from folklore passed down through the centuries. According to legend, Hermann the Recluse was condemned to be walled alive for breaking his monastic vows. To avoid death, he begged his superiors for mercy, promising to write a book containing all human knowledge in one night.

When the magnitude of his promise overwhelmed him, he fell to his knees and invoked the Devil, offering his soul in exchange for help. The Devil agreed, completing the book overnight — and in return, Hermann added a full-page portrait of his infernal benefactor as a token of gratitude.

While this tale cannot be verified, it reveals much about medieval psychology and theology. In the Middle Ages, monks believed that extreme feats of knowledge or craftsmanship might be aided by divine or demonic forces. A book so vast and perfect as the Codex Gigas could not, in the medieval imagination, be produced by mortal hands alone.

The myth also carries a moral message: a warning about human pride and the danger of overreaching. In seeking to rival divine creation, Hermann — like the biblical Lucifer — might have fallen into the sin of hubris. Thus, the legend serves as both a cautionary tale and a spiritual allegory.

A Monk Between Worlds: Faith, Fear, and Redemption

If Hermann was indeed a real person, his life would have unfolded in a time of religious fervor and strict discipline. The Benedictine Rule demanded humility, obedience, and silence. Every act, from copying scripture to tending gardens, was a form of worship. Yet this same devotion often led to deep guilt and fear of sin.

It’s possible that Hermann’s project began as an act of penance. Medieval penitents sometimes undertook lifelong works of devotion — constructing a chapel, copying scripture, or illuminating manuscripts — to atone for their misdeeds. The Codex Gigas could have been Hermann’s chosen offering, a monumental gesture of repentance meant to secure his salvation.

Evidence within the manuscript supports this interpretation. Near the pages containing the Devil’s illustration and the Heavenly City, Hermann wrote in larger letters a confession of sins — pride, envy, lust, gluttony, and even bestiality. Whether these were personal confessions or symbolic warnings remains unknown, but they suggest an awareness of guilt and the hope for forgiveness.

The juxtaposition of the Devil’s image with the Heavenly City of Jerusalem on facing pages may reflect Hermann’s internal struggle — the eternal battle between sin and salvation, temptation and faith.

Scholarly Perspectives: Hermann as an Artist and Scholar

Modern scholars view Hermann not as a damned soul, but as a man of immense intellect and artistic vision. The Codex Gigas includes texts far beyond the Bible: historical works by Josephus, medical treatises, and even magical incantations. This suggests that Hermann was not just a monk, but also a scholar deeply engaged in the knowledge of his age.

In a world where books were rare and education confined to the clergy, Hermann’s mastery of Latin, theology, medicine, and history marks him as an unusually educated man. The inclusion of exorcism formulas and magical texts doesn’t necessarily indicate heresy; rather, it reflects the medieval understanding that faith and science, religion and magic, often coexisted.

His artistic talent also cannot be overstated. The calligraphy, the balance of text, and the ornamental design reveal a trained hand — one familiar with the traditions of illumination. Hermann may have studied at or corresponded with other Benedictine scriptoria across Europe, learning techniques that would make his Codex both functional and majestic.

The Enduring Shadow of Hermann the Recluse

Whether he was a tormented sinner, a genius scholar, or both, Hermann the Recluse has become an enduring symbol of human complexity. He represents the dual nature of the Devil’s Bible Codex itself — at once sacred and profane, divine and human.

His anonymity only deepens the fascination. Few details of his life survive; no other works bear his name. And yet, his creation endures as one of the greatest masterpieces of medieval Europe — a monument that outlived kingdoms, wars, and centuries.

Perhaps that is the greatest irony of all: that a man who may have been punished to silence has spoken more loudly through his book than any monk of his time. His ink became his voice, and his manuscript became his confession — one that still echoes eight centuries later.

Unlocking the Pages: Contents of the Devil’s Bible Codex

The Codex Gigas, better known as the Devil’s Bible, is far more than a single monolithic text. Within its towering 620 pages lies a vast compilation of knowledge from the medieval world — religious, historical, medical, and even mystical. Understanding its contents gives insight not only into the mind of its scribe, Hermann the Recluse, but also into the worldview of 13th-century Bohemia.

Unlike modern books, which focus on one subject per volume, medieval codices often functioned as encyclopedic repositories. The Codex Gigas exemplifies this tradition, incorporating diverse texts that collectively offer a snapshot of contemporary learning and belief.

1. The Latin Vulgate Bible

At its core, the manuscript contains the entire Latin Vulgate Bible, the standard biblical text for Western Europe at the time. This includes:

- The Old Testament, with stories from Genesis to Malachi, recounting creation, the history of Israel, and prophecies.

- The New Testament, detailing the life of Christ, the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles, and Revelation.

What sets this copy apart is not just its size — it is over three feet tall and nearly nine inches thick — but also its illustrations and elaborate initials, which mark important passages. The scribe frequently used decorative spirals, flowers, and animal motifs to highlight the beginning of books and chapters, making the text visually engaging as well as informative.

2. Historical Works

Hermann did not limit himself to religious writings. The Codex includes several important historical texts, such as:

- “Antiquities of the Jews” and “The War of the Jews” by Flavius Josephus, chronicling Jewish history from creation to the fall of Jerusalem.

- The Chronicle of Bohemia by Cosmas of Prague, offering a record of local events and rulers, which provides context for the political and religious life of Bohemia during the 13th century.

These historical texts suggest that Hermann aimed to preserve knowledge, not only of the divine but also of human achievement and civilization.

3. Medical Texts and Remedies

Another remarkable aspect of the Codex Gigas is its medical knowledge. The manuscript contains compilations of works such as:

- Ars Medicinae, a comprehensive guide to diagnosing and treating ailments.

- Medical treatises by Constantine the African, one of the foremost medical scholars of the medieval world.

These sections reveal an unusual blend of empirical observation and mystical practices, typical of medieval medicine. Remedies include herbal treatments alongside incantations, reflecting a belief that the body and soul were intertwined and that healing required attention to both.

4. Magic, Incantations, and Exorcisms

Perhaps the most infamous part of the Codex Gigas are its magical formulas and exorcism texts. These include spells and instructions intended to:

- Ward off demons and evil spirits.

- Cure physical and mental ailments believed to be caused by supernatural forces.

- Invoke protection over individuals or households.

Though modern readers may find these passages alarming, they were common in medieval religious practice. Clerics often employed ritualistic formulas alongside prayers, blending spirituality and superstition into everyday life.

5. Reference Works and Encyclopedic Knowledge

The Codex also functions as a medieval encyclopedia, containing:

- Isidore of Seville’s “Etymologiae”, a vast compendium of classical and medieval knowledge covering language, nature, theology, and science.

- Lists of alphabets in Hebrew, Greek, and Slavic scripts.

- Local records, calendars, and necrologies, noting the deaths of monks and prominent figures.

This diversity shows that Hermann sought to make the Codex a comprehensive repository, perhaps fulfilling his legendary ambition to include all human knowledge in a single volume.

6. Illustrations: Heaven, Hell, and the Devil

The manuscript’s illustrations are as compelling as its text. The most famous image is the full-page depiction of the Devil, seated, green-faced, with horns and claws. On the opposite page lies the Heavenly City, depicting angels, saints, and the New Jerusalem.

These images are not merely decorative; they symbolize moral duality — good and evil, salvation and damnation — and underscore the manuscript’s spiritual purpose.

Other illustrations include:

- Creation scenes from Genesis, with Earth, Heaven, stars, and the Moon vividly portrayed.

- Ornate initials marking the beginnings of the Gospels and other sections, combining artistry and meaning.

The visuals make the Codex not only a book of knowledge but also a theological and artistic masterpiece.

7. Organization and Structure

Despite its massive scope, the Codex is carefully structured. Hermann arranged texts logically, beginning with the Bible, followed by historical works, medical texts, magical formulas, and finally, local records and reference material.

The manuscript’s uniform calligraphy and meticulous spacing make it remarkably readable, even by modern standards. Each page is a testament to the scribe’s discipline and dedication, blending practicality with aesthetic beauty.

Why Its Contents Matter Today

The Codex Gigas offers modern scholars and historians a rare glimpse into medieval thought, spirituality, and scholarship. It shows how knowledge was preserved, transmitted, and often interwoven with legend, morality, and superstition.

From the Bible and historical chronicles to medical remedies and magical formulas, the Codex encapsulates the medieval worldview, where religion, science, and folklore were inseparable. Its enduring fascination lies not only in its size or imagery but also in the sheer ambition of its creation — a human endeavor so monumental that it inspired legends of pacts with the Devil.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Devil’s Bible Codex

Ultimately, the Devil’s Bible is a remarkable blend of the sacred, scholarly, and supernatural. It showcases the imagination, skill, and dedication of its creator while preserving centuries of knowledge, belief, and artistry. Nearly 800 years later, the Codex Gigas continues to fascinate, inspire, and intrigue as a timeless symbol of human curiosity and ambition.